A Master Naturalist works to protect and celebrate the small wonders of Warner Park

Notes from the Field is a blog series profiling the people and programs supporting NRI’s mission and making a difference in communities across Wisconsin.

No one speaks as adoringly of leeches as Kathlean Wolf. Sitting under a picnic shelter in Madison’s Warner Park, the Master Naturalist and president of Wild Warner rattles off the names and quirks of each of the leeches she keeps in a three-gallon jar in her home. There’s Noo Leech, recently plucked from a turtle; Ribbon Leech, who swims like a dancer; and Beautiful Leech, whose natural charm and fetching good looks enamored Kathlean immediately.

“When I first got her, she was full of her most recent meal, and when she was backlit, you could see her entire gut system. And it was just gorgeous. She was so pretty.”

Kathlean’s love of the unsung is evident on our hike through Warner Park. Veiled in mosquito netting, we meander through the woods as she points out what’s new (a felled hackberry tree) what’s old (plastic bottles), and what’s edible (grape leaves). We stop at what looks like a lightning-blasted tree.

“This is one of the two trees that got me hooked on this woods. You see that blue color?”

She points to what look like black burns. A closer inspection reveals that the burns aren’t black, but teal.

“That’s actually a fungus.” Kathlean explains that the pigment comes from the Chlorociboria genus of fungi—known as “green stain” fungi—and the tinted wood was historically used to color wood cuttings. She motions to the base of the tree.

“My daughter and I came out here February of the first year we had lived here. I saw this blue, and then there was a piece of plywood lying there. I pulled it up, and there was this beautiful yellow slime mold in there. And it was just gorgeous and all the complicated little networks that it had built and everything. So that was it. It’s February, and I just moved in, and I was hooked.”

Luckily for Kathlean, she doesn’t need to travel far to get her slime mold fix. She lives right across the street from the park on the city’s north side and regularly spends time exploring and tending to the woods. She goes slowly, greeting old friends (a fallen oak) and introducing herself to new ones (a small fungus, or a flower). It isn’t hiking, or even taking a walk. Kathlean calls it “taking a look.”

“It’s just way more cool. The slower you go, the more you not only see but hear.”

Learning the landscape

Kathlean has had a lot of practice with noticing the small and subtle things. Growing up in Utah, she spent much of her time outdoors exploring, climbing mountains, and visiting national parks. She became attuned to an unforgiving landscape: one that was dry, mountainous, and presented the very real threat of getting lost and not being found. When she moved to Wisconsin and next door to Warner Park in 2013, she had to readjust to an entirely new environment. For one, there were no mountains. There was lots of water. And there were bright red cardinals seemingly everywhere.

“The birds in Utah are cryptic. They’re hiding because it’s desert. Everything’s tan. There’s competition for all the resources, especially water. You don’t want to be highly visible—that’s dangerous; you’re going to get eaten.”

Captivated with the ecosystem of her new home, Kathlean wanted to learn more. A Wild Warner member who was also an instructor with the Master Naturalist program encouraged her to apply to the program. It was 2016, and at the time, Kathlean was on disability awaiting knee replacements. Despite maneuvering on crutches during field trips to see a drumlin or open oak savannah, Kathlean loved the program, particularly how it was structured.

“It was the perfect teaching format. You’ve got two hours in the morning of learning from the great big resource manual that they gave us… and then two hours of going out to Warner Park or going on a field trip to another park.”

The 40-hour training courses are offered throughout the state and include units on geology, ecology, wildlife, interpretation, water, aquatic life, and human impacts on the environment. Participants synthesize all they’ve learned in a capstone project of their choosing.

Kathlean drafted a habitat map of Warner Park to serve as a guide for nature exploration and also indulged her interest in fungi. “That was the year of mushroom photography.” Over the course of three months, she documented nearly 100 species of slime molds, protists, and fungi living in the little woodland across from her home.

Beyond encouraging her curiosity, the program connected Kathlean with the people and resources to continue learning. She knows who to contact to discuss the Sisyphean enterprise of buckthorn removal, for example, or to help identify urban wildlife.

She also has the title that comes with the training, which lends legitimacy to her projects and the hikes she leads around Warner Park. “People appreciate knowing it’s not some random person. It’s a Master Naturalist.”

But Kathlean notes that the title doesn’t mean she knows everything—far from it. Her indefatigable sense of curiosity and exploration often lead her to ask questions to which she doesn’t know the answers. As a Master Naturalist, though, she knows who to ask or what resource to consult to find the answers.

Taking care of the park together (while being apart)

Since becoming a Master Naturalist four years ago, Kathlean has been busy helping others appreciate Warner Park as much she does.

In addition to serving as President of Wild Warner, Kathlean organizes and participates in environmental restoration and education activities throughout the park. She has led public hikes and foraging excursions and regularly removes trash and invasive plants. She also takes photographs and writes nature articles for the Northside News.

When the pandemic escalated in spring, however, work parties and group hikes were suddenly off the table. So, Kathlean got creative.

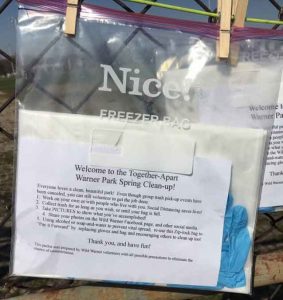

In April, she organized a physically distanced cleanup event, the Together-Apart Earth Day Cleanup, where she tacked four pairs of gloves, several 30-gallon garbage bags, and instructions onto a chain link fence, advertising on the Wild Warner Facebook page and Nextdoor.com. Over the course of a week, volunteers collected more than twenty bags of trash from the creek.

She created a similar setup for garlic mustard, leaving bags and instructions for removal at the trails leading to the woods.

She also began a new project this summer: protecting turtle eggs. “There was a big snapping turtle nest here last year. And it was like 40, 50 eggs. Huge old mom. And I find this out by finding it totally destroyed. So that’s when I started to look into it.” Following a design suggestion from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Kathlean installed cages over the nests to defend against skunks, raccoons, and foxes looking for an easy meal.

Kathlean’s love for Warner takes shape in projects like these across the park. A bag of weeds, a newly planted hazelnut bush, wire mesh folded carefully over a clutch of eggs are all evidence of her attention and care. She just hopes she can mobilize more people to become active stewards. “I know we have a big base of people who are interested in the park, who love the park, who would love to restore nature. How do you get the volunteerism to get going?”

Sounds like a good challenge for a Master Naturalist.