When the celebrated, fleecy snows of December transform into the much-maligned ice of March, many Wisconsinites turn to salt to make walkways and roadways safe. But unlike the ice it melts, salt does not conveniently disappear after use. Where then does it go?

Lakes, rivers, streams—and as Ken Bradbury, director of the Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey, discovered—your drinking water.

Bradbury made the finding as part of a larger study on water quality in a new, rural subdivision in eastern Dane County. From 2001 to 2015, Bradbury, then-graduate student Jeff Wilcox and others sampled groundwater for a number of contaminants including chloride, one of the components of salt.

“The main object of this work was to find out what a rural subdivision does to groundwater when it’s built,” Bradbury said. “The focus was not necessarily on chloride, but chloride was one of the things we looked at.”

Bradbury and his team took water samples prior to and following the construction of the subdivision from both shallow and deep wells across the 78-acre lot. Some wells were situated along woodlots, others near roads or down from septic tanks.

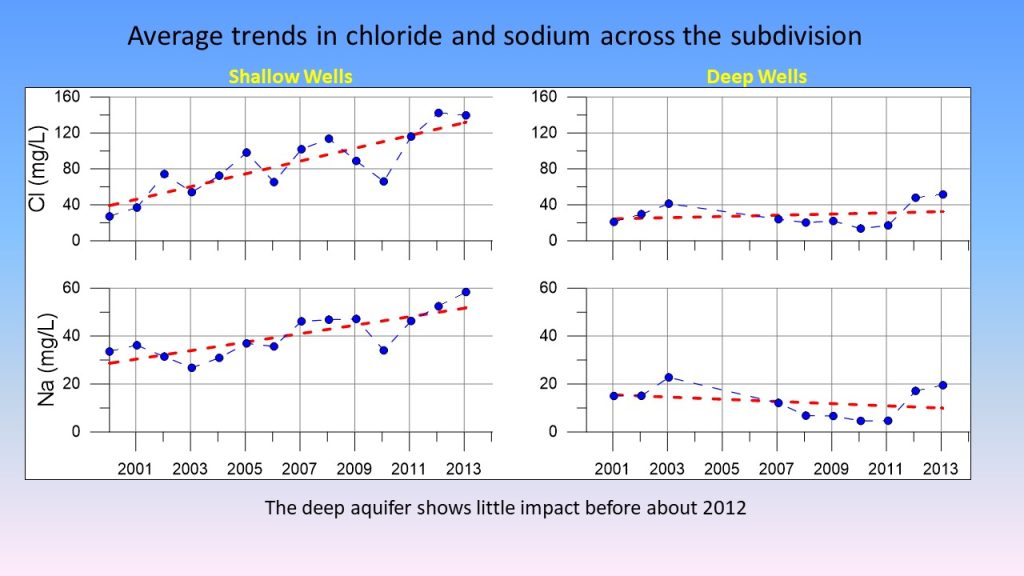

The shallow wells showed the greatest impact.

“There was a very steady trend of increasing chloride of about a factor of three,” said Bradbury.

One of the shallow wells situated near a busy intersection with a state highway reported chloride concentrations over 400 mg/L, which far exceeds the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s secondary drinking water standard of 250 mg/L. In winter, it’s an area likely treated with lots of salt, which eventually seeps into shallow groundwater.

The result from the deeper wells were less dramatic—at least initially.

“In the deep wells, there was less of a trend,” said Bradbury, “Although we do see when we get to the end of our sampling period that the deep wells are beginning to rise as well.” The lag isn’t surprising given that it takes longer for water to reach deeper wells.

So where is all that chloride coming from?

Road salt is one culprit. Bradbury notes that chloride can also come from onsite septic systems, water softeners, agricultural fertilizers, manure landspreading and natural salt deposits. Chloride also doesn’t get filtered out by soil. Where the water goes, it goes.

“Chloride is mobile in groundwater systems,” said Bradbury. “It doesn’t adhere to soil particles; it pretty much moves with the groundwater.”

This means that just as chloride can enter an aquifer, it can also leave an aquifer. A big summer rain could flush it from a shallow aquifer to a deeper one or to another discharge point, like a river or lake. Freshwater ecosystems, however, are just that—freshwater—and aquatic life in these ecosystems can only tolerate so much salt. Studies have shown that higher concentrations of chloride can kill zooplankton and reduce the size of fish.

So while chloride may move around, it doesn’t disappear, making it important to limit the amount of salt introduced onto the landscape.

Wisconsin Salt Wise, a coalition of organizations working to reduce salt pollution across the state, offers several tips for using less salt during winter:

- Shovel before you salt. If you are able, clear walkways before snow turns to ice. Less snow means less salt.

- Scatter; don’t dump. You only need a mug of salt for 10 sidewalk squares or a 20-foot driveway. Make sure there is space between granules and avoid creating piles.

- Be mindful of the temperature. Road salt doesn’t work when temperatures drop beneath 15 °F. Switch to a different treatment or use sand.

How much salt is in your drinking water? Check out the Center for Watershed Science and Education’s Well Water Quality Viewer to see private well data in Wisconsin.

Watch Ken Bradbury discuss his research with Wisconsin Salt Wise during Salt Awareness Week.