This story was originally published in the Wisconsin Towns Association Magazine. It has been edited and republished here.

For the last four years, the Town of Campbell on French Island has been under an interim drinking water health advisory due to PFAS contamination. According to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, have been detected at elevated levels in municipal wells, private drinking water, and groundwater.

Contamination events like the one on French Island are confusing, scary, and even political. That’s why targeted education, outreach, and communication are needed to ensure members of the public have the information they need, especially in times of uncertainty. And the Town of Campbell is not alone. Other areas, including Madison, Peshtigo, and Stella, have advisories related to PFAS concerns as well.

To help address these concerns, UW–Madison Division of Extension uses research findings to provide community support and information about emerging contaminants. Some of these efforts involve community workshops, language accessible materials, online and paper fact sheets, and cutting-edge research.

Helping communities understand PFAS and other contaminants

In her role as the Extension Emerging Contaminants Outreach Specialist, Anya Jeninga works with partners to increase access to information. She helps communities stay informed on emerging contaminants and understand what can be done about them. As a part of this work, she is an associate investigator on a project working to expand PFAS testing in Wisconsin and to build a toolkit for county health departments to use when they have elevated PFAS levels in their jurisdiction. She also recently released a story map on PFAS in Wisconsin to help inform Wisconsinites about the chemicals and how they can take action.

“When it comes to PFAS, a lot of folks are just learning about the chemicals, their sources, and their impacts,” notes Jeninga. “And to make matters more confusing – most folks don’t know if their water is a significant PFAS source,” Jeninga said.

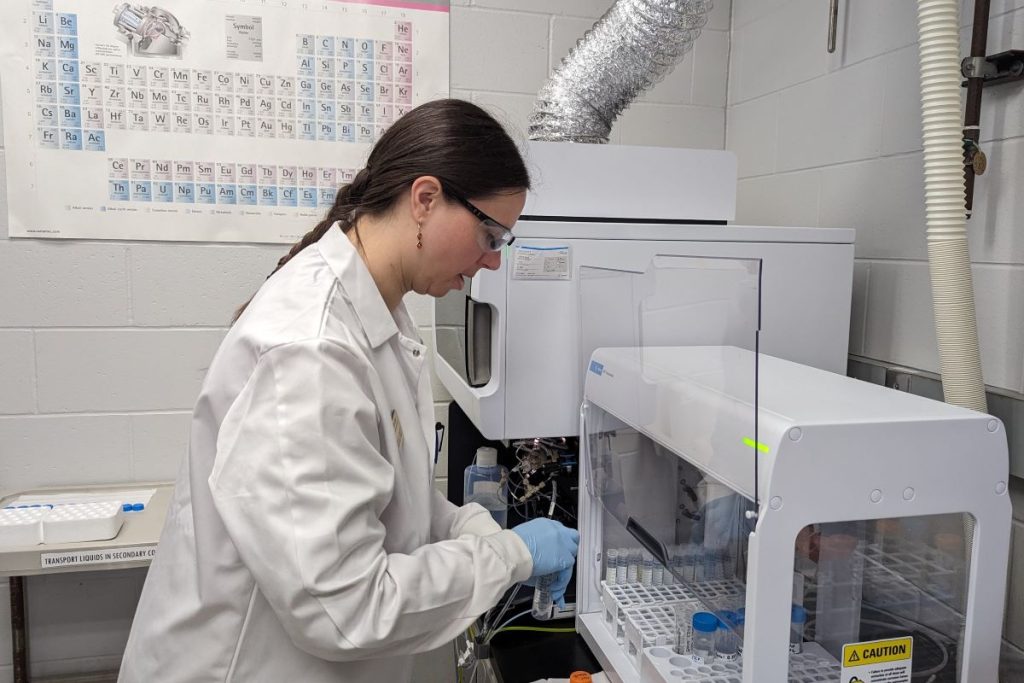

Kevin Masarik is an Extension Groundwater Specialist and Director of the Center for Watershed Science and Education at UW-Stevens Point. The center houses the state-certified Water & Environmental Analysis Laboratory, which analyzes private well water samples sent in by Wisconsin residents. The center recruits staff to help members of the public interpret the results of their well water testing, information which contributes to the Wisconsin Well Water Viewer, a free, interactive map that depicts well water quality in all Wisconsin counties.

“Currently, we don’t offer PFAS testing, but we are hoping to integrate PFAS testing into our Extension programming efforts in the near future. In addition, we are investigating other potential screening tools and funding opportunities to allow us to offer PFAS testing at a more affordable price point than what is currently available,” notes Masarik. “Right now there are only a handful of labs that test for PFAS in the state and private well water quality testing for PFAS can cost between $300 and $400, making it cost prohibitive for many.”

What are PFAS?

PFAS originate from many sources, including firefighting foams, consumer products, food wrappers, nonstick cookware, and water and greaseproof clothing. PFAS are also commonly used in different industrial processes, like chromeplating metals.

PFAS can enter our drinking water, private wells, and groundwater aquifers through runoff from biosolids containing PFAS, leaching from landfills and septic systems, and from industrial waste discharge. Additionally, animals and plants exposed to high levels of PFAS may accumulate the chemicals and pass them when they are consumed. PFAS have also been shown to enter our air through industrial processes or the breakdown of some carpets.

While the health impacts of PFAS are not fully understood, research has shown that exposure to high levels of the chemicals can impact the thyroid, reproductive health, cholesterol, vaccine efficacy, and infant birth weights, and can increase the risks for some cancers.

Complicating matters further is the fact that PFAS are difficult to monitor because testing requires professionals and expensive equipment. Many water sources across the state have not yet been tested for the chemicals, and when PFAS testing is available, interpreting the results can be complicated.

Making sense of PFAS data

In her work, Jeninga has found a lot of confusion around PFAS and test results. To help address this confusion, Jeninga developed a fact sheet designed to help private well owners understand their test results.

This is something Karl Green, a geologist and Program Manager for Extension’s Local Government Education Program, knows all too well. “Water testing can be confusing for landowners and municipalities alike. Common water tests, especially those done during transitions in home ownership, only sample for more common contaminants, usually nitrate, nitrite, and bacteria. However, these samples do not test for substances like PFAS or volatile organic compounds. Residents must understand which test they are using, and what it is designed to detect,” notes Green.

Moreover, understanding the results of a water test is an entirely different problem. “It’s all chemistry, and that stuff is not easy to interpret. Depending on the lab and how they report, it can be very confusing,” says Green.

Green hosted a webinar on April 16 on PFAS sources, impacts, and potential funding opportunities for local government officials. Jeninga was one of the speakers, along with representatives from the Town of Campbell.

Even as scientists work to uncover the mysteries of PFAS and Extension expands its educational efforts, residents can use the wide array of Extension’s water quality resources to stay safe and informed.

“I’ve seen a lot of responses to environmental contamination, and I’ve seen the confusion that happens whenever there’s a new site, between the residents and state agencies and the local partners they work with to respond. I’m excited to help work on that, and help make that whole process smoother,” says Jeninga.

Across Extension, our collaborators are enthusiastic to work together to create more public materials, including specific outreach on PFAS contaminants.

If you’re curious about testing your water or learning more, visit the Center for Watershed Science and Education or a local health department near you.