The Midwest houses some of the most extensive and diverse water resources in the United States. Perhaps one of its little known resources is its groundwater supply, which supplies fresh drinking water to thousands of Wisconsinites. However, groundwater is highly susceptible to contamination from both human and environmental hazards, so Extension has been working hard to ensure surveillance and safety communication on contamination.

What are environmental contaminants?

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) defines contaminants as hazardous materials, including solids, liquids, and gases, which pose a threat to human health and environmental wellbeing. Generally, these contaminants present themselves in drinking water, private wells, and groundwater reservoirs. Bacteria, nitrate, and lead are a few examples.

Emerging contaminants are new environmental contaminants that have not yet been thoroughly evaluated by the scientific community. PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) are particularly dangerous emerging contaminants, and are still being researched by scientists.

PFAS are especially difficult to track because PFAS testing requires professionals and expensive equipment. Not to mention that PFAS occur in very small, yet dangerous, amounts, raising the risk of inaccurate water testing results. There are only a few labs in Wisconsin that offer testing for PFAS; however, Extension resources are mitigating concerns about PFAS through community outreach efforts.

Kevin Masarik is the Extension Groundwater Outreach Specialist and Interim Director for the Center for Watershed Science and Education at UW–Stevens Point. While the Center doesn’t currently offer PFAS testing, it promotes community outreach programs to facilitate water testing at the community level.

“One of the barriers to getting a well tested is not knowing what to test for, or not knowing where to send a sample. So, by working with these communities to overcome some of those barriers, it’s a way for people to get their water tested,” says Masarik.

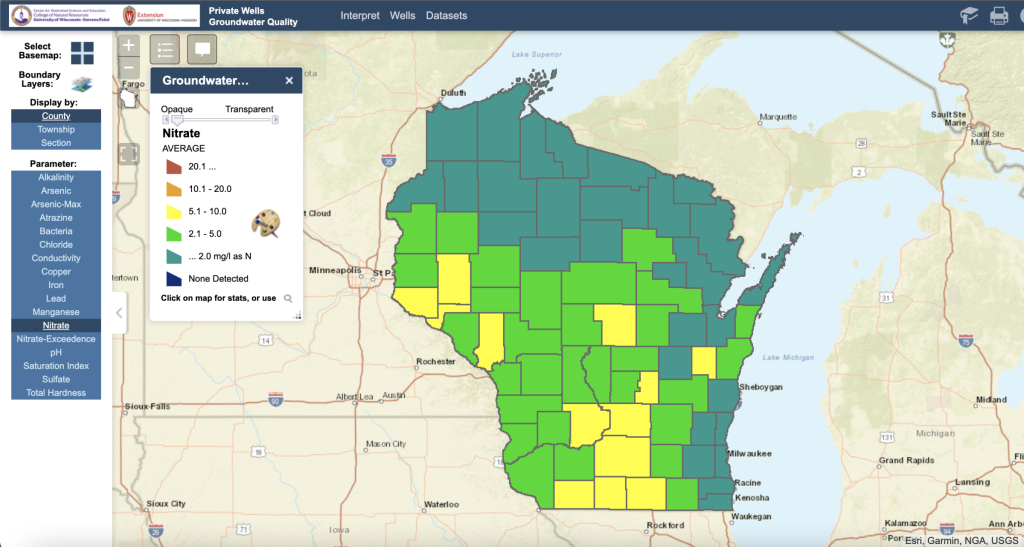

The Center houses the state-certified Water & Environmental Analysis Laboratory, which will analyze well water samples sent in by Wisconsin residents. The Center recruits staff to help the public interpret the results of their well water testing, information which contributes to the Wisconsin Well Water Viewer, a free, interactive map that depicts well water quality in all Wisconsin counties.

Extension professionals also work with local government and state agencies to conduct outreach with communities on emerging contaminants. Karl Green, a former geologist and Program Manager for Extension’s Local Government Education Program, has worked with Wisconsin’s municipal leaders on water quality issues.

In his experience, water testing confusion begins before a sample is even taken. Green emphasizes that water tests, especially those done during transitions in home ownership, only sample for certain compounds, usually nitrates, nitrites, and bacteria. However, these samples do not test for substances like PFAS or volatile organic compounds. Residents must understand which test they are using, and what it is designed to detect.

Moreover, understanding the results of a water test is an entirely different problem.

“It’s all chemistry, and that stuff is not easy to interpret. Depending on the lab and how they report, it can be very confusing,” says Green.

Anya Jeninga, recently hired as Extension’s Emerging Contaminants Outreach Specialist, will soon begin work on a fact sheet designed to help well owners, with and without science education backgrounds, understand their test results. In doing so, Extension hopes to encourage more people to test their water.

Why is it so difficult to communicate about emerging contaminants?

Contamination events are confusing, scary, and even political, which means that specific communication strategies are needed to ensure the public feels safe and informed, even in times of uncertainty.

Science requires a long process of observing, measuring, and coming to consensus among hundreds of researchers; however, emerging contaminants’ newness means that they have not undergone that process yet.

Jeninga says, “Emerging contaminants as a field is really important because we need to be on top of all of the new research that’s out there … because we can’t give people the best advice to make an educated decision about their risk on emerging contaminants unless we know the most recent stuff that’s happening.”

So, Extension has been putting its professionals in communities where they can provide support and accurate information about emerging contaminants. Some of these efforts involve community workshops, language-accessible materials, and online and paper factsheets.

It also involves conversations between Extension educators and citizens from diverse educational backgrounds.

“Everybody’s got a different understanding. So, for an educator … putting it in the form of a story that gets them to really see that picture that a geologist can see—that’s a challenge, but I think it’s important,” says Green.

At the Center for Watershed Science and Education, Masarik and his fellow educators are focusing on educating the public by using positive messaging to promote self-efficacy and confidence in water testing.

“There are some behavioral hurdles we try to overcome. I never like to use fear as a motivating factor for testing,” says Masarik, “if the fear you instill is greater than people’s ability to deal with that fear, it can turn people off to doing what you want them to do [test water].”

Even as scientists work to uncover the mysteries of PFAS and Extension expands its educational efforts, residents can use the wide array of Extension’s water quality resources to stay safe and informed.

“I’ve seen a lot of responses to environmental contamination, and I’ve seen the confusion that happens whenever there’s a new site, between the residents and state agencies and the local partners they work with to respond. I’m excited to help work on that, and help make that whole process smoother,” says Jeninga.

Across Extension, our collaborators are enthusiastic to work together to create more public materials, including specific outreach on PFAS contaminants.

If you’re curious about testing your water or learning more, visit the Center for Watershed Science and Education or a local health department near you.